- Data Visualization With Ggplot2 Cheat Sheet

- Ggplot2 Sheet

- Rstudio Ggplot2 Cheat Sheet

- Ggplot2 Cheat Sheet R

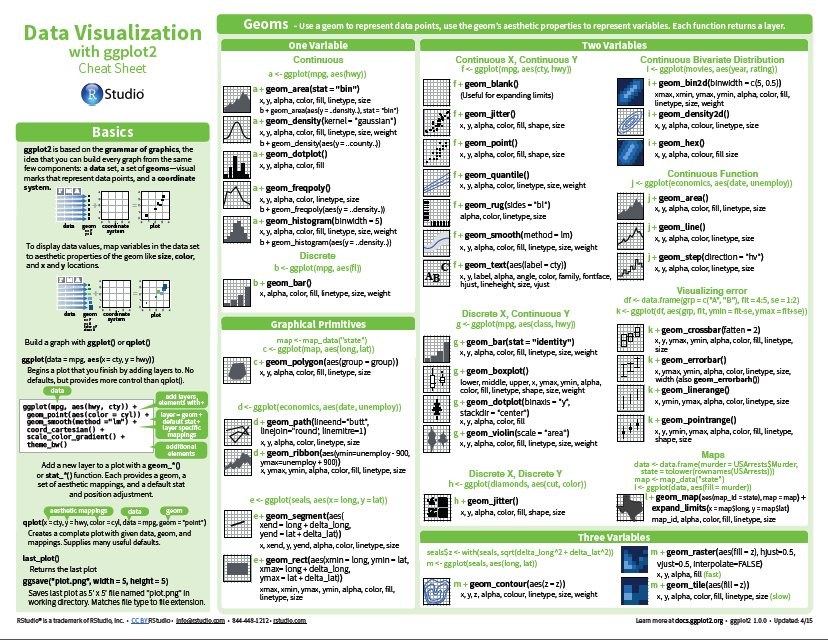

As shown in Figure 2, multiple shapes can be used as points. The Data Visualization Cheat Sheet lists several shape options` geomsmooth adds a fitted line through the data. Method=lm specifies a linear regression line. Method=loess creates a smoothed local regression curve. Se=FALSE removes the shaded 95% confidence regions around each line. Ggplot2 uses the basic units of the “grammar of graphics” to construct data visualizations in a layered approach. The basic units in the “grammar of graphics” consist of: The data or the actual information that is to be visualized. The geometries, shortened to “geoms”, which describe the shapes that represent the data. These shapes can be dots on a scatter plot, bar charts on the graph, or a line to plot the data. Data Visualization with ggplot2:: CHEAT SHEET ggplot2 is based on the grammar of graphics, the idea that you can build every graph from the same components: a data set, a coordinate system, and geoms—visual marks that represent data points. Basics GRAPHICAL PRIMITIVES a + geomblank (Useful for expanding limits).

In the last chapter, we visualized the relationship between per capita GDP and life expectancy. You might have wondered how time fits into that association. In this chapter, we’ll explore life expectancy and GDP over time.

The following ggplot2 cheat sheet sections will be helpful for this chapter:

- Geoms

geom_path()

- Scales

The lubridate package is a helpful tool for working with dates. We’ll use some lubridate functions throughout the chapter. Take a look at the lubridate cheat sheet if you’re not already familiar with the package. Voxengo for mac.

Not all time series are alike. In some situations, you’ll be interested in a long-term trend, but in others you’ll want to highlight short-term changes or even just individual values. In this chapter, we’ll cover various strategies for dealing with these different scenarios.

First, we’ll talk about the mechanics of date scales, which are useful for time series.

6.1 Mechanics

6.1.1 Date/time scales

Sometimes, your time series data will include detailed date or time information stored as a date, time, or date-time. For example, the nycflights13::flights variable time_hour is a date-time.

When you map time_hour to an aesthetic, ggplot2 uses scale_*_datetime(), the scale function for date-times. There is also scale_*_date() for dates and scale_*_time() for times. The date- and time-specific scale functions are useful because they create meaningful breaks and labels.

flights_0101_0102 contains data on the number of flights per hour on January 1st and January 2nd, 2013.

Just like with the other scale functions, you can change the breaks using the breaks argument. scale_*_date() and scale_*_datetime() also include a date_breaks argument that allows you to supply the breaks in date-time units, like “1 month”, “6 years”, or “2 hours.”

Similarly, you can change the labels using the labels argument, but scale_*_date() and scale_*_datetime() also include a date_labels function made for working with dates. date_labels takes the same formatting strings as functions like ymd() and as_datetime(). You can see a list of all formatting strings at ?strptime.

We’ll use date_labels to format time_hour so that it doesn’t take up as much space.

6.2 Trends

6.2.1 One response variable

gm_combined is the same Gapminder data you saw in the previous chapter. Previously, we investigated how life expectancy is associated with per capita GDP. Now, we’ll ask a more obvious question: how has life expectancy changed over time?

First, let’s just look at a single country: South Africa.

Adding geom_line() will make it easier to connect the dots and see the trend.

It looks like life expectancy started to fall around the time apartheid ended. We can add a reference line to check our hypothesis.

We could remove the points and just use a line, but the points are helpful indicators of the actual data. Generally, the more points you have, the less important it is to keep the points. For example, the following plot shows life expectancy for South Africa using the gm_life_expectancy, which contains yearly data. We’ve also filtered the data to only include the years 1800 to 2015, because the data after 2015 is based on projections.

The points are so close together that they form their own line, and so removing geom_point() doesn’t really affect the appearance of the plot.

Including points is important, however, if your data is irregularly distributed. For example, say our data only included two points between 1800 and 1950, but was yearly after 1950. In this situation, it would be important to use both points and lines to show the discrepancy in the amount of data.

There are two major dips in life expectancy in our plot. The first is the result of the 1918 influenza pandemic. The second, as we already pointed out, started around the end of apartheid. One hypothesis for this dip is that data reporting procedures changed when the South African government changed. Maybe the apartheid government systematically under-sampled non-white groups who may have had lower life expectancies. Another hypothesis is that changes in government led to general upheaval, which somehow affected life expectancy.

To further investigate, we’ll compare South Africa to its neighbors during this time period.

When you have multiple time series, adding geom_line() makes it easier to group each series together.

In the previous chapter, you learned how to reorder and align legends to make it easier to match lines with labels. Directly labeling the lines makes it even easier to connect a line with its label.

We removed the legend by using guides(color = 'none').

Interestingly, all four countries experienced similar declines in the early 1990s. This suggests that South Africa’s decline was not related to the end of apartheid. Next, we might ask if this dip occurred in all of Africa, which brings us to the next section: visualizing distributions over time.

6.2.2 Distributions over time

We can join gm_life_expectancy with gm_countries to look at all countries in Africa.

There are 54 countries listed under the “Africa” region in the data.

Plotting all the data at once is messy, but you can see that many countries experienced the same dip in the 1990s. You can also see that the countries with high life expectancies didn’t experience at dip at all, and that many countries experienced dramatic downward spikes due to single events.

One of these downward spikes is the Rwandan genocide.

Another is the Libyan Civil War.

Highlighting specific lines of interest is a useful way to compare select values to the rest of the data. We could try highlighting the subset of countries in southern Africa that we looked at earlier.

Data Visualization With Ggplot2 Cheat Sheet

You can see that the countries we highlighted weren’t the only ones that experienced the dip in the 1990s.

To get a sense of the trend for all of Africa, we could add a smooth line.

You can see a slight dip around the 1990s. However, this smooth line doesn’t capture the amount of variation in trends. Africa is a massive continent. Maybe dividing it up further will be more informative.

We can use region_gm8 to compare North Africa to Sub-Saharan Africa.

Most of the data lies between 40 and 80 years. We’ll use coord_cartesian() to zoom in on this region.

Individual lines are now easier to see. There aren’t very many countries in North Africa, but they all have relatively high life expectancies. All of the countries that experienced a severe dip in life expectancy in the 1990s are in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Now, we can try a smooth line for each region.

There’s a sharp contrast between North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa. The dip in Sub-Saharan African life expectancies is likely due the HIV/AIDS pandemic, which affected most of Sub-Saharan Africa severely, but was particularly bad in the southern countries that we looked at earlier.

In other situations, you may want to use the techniques covered in the Distributions chapter. For example, you might be curious how the distribution of life expectancies for African countries has changed over time. Box plots are a good option.

6.2.3 Two response variables

So far, we’ve encoded time as position along the x-axis and a response variable, life_expectancy, along the y-axis. What if we want to encode a second response variable? It would be interesting to see how both life expectancy and per capita GDP have changed over time.

geom_path() is a useful way to represent a time series with two response variables. Unlike geom_line(), which connects points in the order they appear along the x-axis, geom_path() connects points in the order they appear in the data. We can use this feature of geom_path() to represent a time series without actually plotting time along an axis.

Here, we’ve plotted gdp_per_capita and life_expectancy for South Africa using geom_path(). We arranged the data by year so that the earliest years are plotted first.

To read a geom_path() plot, you follow the line’s path through the plot space, but you can’t currently tell which end of the line is the starting point. We’ll add a dot to the end of the line indicating the endpoint.

Sometimes, you’ll want to plot individual points as well as the path line. We’ll make the last point bigger to indicate that it’s the endpoint.

Now, it’s clear that the line starts in the lower left corner. Both life expectancy and per capita GDP increased until around $11000. Then, life expectancy continued to grow, but per capita GDP shrank. Around $9025, this trend reversed. Life expectancy fell when per capita GDP increased. Finally, both started increasing again.

You still can’t match points on the path to specific years. Labeling inflection points is helpful.

In 1980, per capita GDP started going down, but life expectancy kept increasing. As a response to apartheid, the United States and other countries imposed sanctions against South Africa in the 1980s. The campaign to divest from South Africa also gathered speed in the 1980s. Both the sanctions and the divestment campaign likely caused the per capita capita GDP to drop. Notice that the trend reversed in 1995.

We can also use alpha to encode year.

Directly labeling points instead of using a legend makes the plot easier to decode. At a minimum, you should label the starting and ending points.

Again, labeling inflection points is helpful.

6.3 Short-term fluctuations

In the mechanics section of this chapter, you saw the following plot.

You might wonder why we used geom_col() to represent a time series. Here’s the same plot using geom_line() and geom_point().

From both plots, you can see that most flights occur in the early morning and around 4pm, but notice that we’re actually treating time like a discrete variable in this situation. We’ve counted the number of flights for each hour, and so it’s useful to be able to connect a number of flights with a specific hour. Columns make it easier to connect numbers of flights to specific hours.

Vertical segment plots using geom_segment() can also be helpful for some time series data. Say we want to understand what the first week in January looked like.

geom_point() and geom_line() produce the following plot.

You can see that each day is shaped similarly. However, you can’t tell that there are actually no flights for a couple hours each night.

geom_segment() does a better job of showing the gaps between days. Segments also make it easier to perceive each day as a group to compare against the others. Another advantage of geom_segment() is that we can use color to encode a categorical variable.

In this case, there’s no long-term trend we’re interested in. Instead, we want to understand short-term fluctuations, and we care about individual values. In these situations, geom_col() and geom_segment() are good options.

6.4 Individual values

Sometimes, you’ll want to display time on the x-axis like a time series, but you won’t actually care about displaying any kind of trend.

The famines dataset from dcldata tracks major famines across time.

There’s no obvious relationship between time and deaths due to famines.

Even though there’s no trend, this data is still interesting if you’re curious about individual famines.

The above plot only uses the start date, but we also have the length of the famines. We can treat the x-axis as representing year generally and encode the length of a line as the length of the famine.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the “grammar of graphics”

- Produce scatter plots, boxplots, bar graphs, and time series plots using ggplot.

- Set universal plot settings.

- Modify the aesthetics of an existing ggplot plot (including axis labels and color).

- Build complex and customized plots from data in a data frame.

We start by loading the required packages. ggplot2 is included in the tidyverse package, and is the current standard for data visualization in R. Authored by Hadley Wickham, gg stands for “Grammar of Graphics.” In learning ggplot2, you may find the following cheat sheet to be a helpful reference.

Overview

Basic grammar

Hadley’s Grammar of Graphics is outlined in detail in this article. Here, he illustrates his principles using a small data set similar to the following:

To visualize any data set using the Grammar of Graphics, it helps to understand the 3 components of which any graph is comprised:

- Geoms

- Scales

- Data columns

Geoms are the visual entities that we see on a graph. In the image below, we see three examples of geoms: a circular point, a bar, and a line:

Scales control how the data columns map to the aesthetic attributes of the geoms. For example, is the point geom yellow or blue? Is it large or small? Is it high or low? Left or right? These aesthetic attributes are respectively controlled by the color, size, y, and x scales:

Additional scales in ggplot2 are:

- shape

- linetype (for the line geom)

- fill (for the bar and point geoms)

Any plot created with ggplot2 requires these ingredients. To create a plot, one must specify the desired geom; which data variables are to be aesthetically mapped to the geom; and the scales to use to control the mapping. The skeleton of any ggplot2 command is as follows; parts in italics are to be replaced with specific data variable names, geoms, and scales:

ggplot(data = nameofdata) + geom_nameofgeom(aes(scale1 = variable1, scale2 = variable2))

At a minimum, most geoms require the x scale.

Let’s begin by mapping A and B to the point geom on a Cartesian plane. Note in ?geom_point that two scales are required for aesthetic mappings to point geoms, x and y:

We can employ other scales outside of aesthetic data mappings. For example, if we want to change the aesthetic mapping of the above scatterplot by changing the shape, color, and size scale, we can do so with the following:

Coreldraw for mac os torrent. Notice in the above code that the scales that are not mapped to data are outside the aes() command.

As an aside, looking at the ?shape help file, we can find code to see all possible shapes:

Now suppose we want to aesthetically map other variables with the shape, color, and size scales. We must now put these specifications inside the aes() command and specify the variables we wish to map. Consider the following code, and note the different looks, error messages and warnings that appear when attempting to apply aesthetic mappings using various scales depending on the data type. In ggplot-speak, “continuous” refers to quantitative data in general; while “discrete” refers to categorical data:

Challenge

Re-create the following plots:

Note some interesting concepts illustrated here:

- Continuous (numeric, quantitative) variables should be mapped using size or color scales; these are the scales that can encode quantity.

- Discrete (categorical) variables should be mapped with shape or color scales; these are the scales that are best used for indicating “categories.”

Layers

A very important aspect of the ggplot2 package is the idea of layers. Aesthetic mappings to different geoms can take place simply by specifying additional mappings with a + sign. For example, suppose we want to create the above scatterplots with points and lines. This requires two aesthetic mappings: one from the data to the points geom, and one from the data to the lines geom. We can see this in what follows. Note that because both geom_point() and geom_line() rely on the same aesthetic mapping, we could simplify the code by specifiying the appropriate mapping in the initial ggplot() command. The following two lines of code are equivalent:

Challenge

Re-create the following plots. What happens if you try to map variable C to geom_line() using the size scale?

Analysis of ecology data

Now let’s start visualizing some real data. If not still in the workspace, load the data we saved in the previous lesson.

When plotting scatterplots, ggplot likes data in the ‘long’ format: i.e., a column for every dimension, and a row for every observation. However, when plotting barplots where the height of the bars are counts or percents, pre-aggregated data (e.g., the output from a series of dplyr commands) may work better. Well-structured data will save you lots of time when making figures with ggplot.

To create a scatterplot of hind foot length versus weight, we need to:

- bind the plot to a specific data frame using the

dataargument

- define aesthetics (

aes), by selecting the variables to be plotted and the scales to define the geoms

- add

geoms– graphical representation of the data in the plot (points, lines, bars). To add a geom to the plot use+operator

Recall that the + in the ggplot2 package allows you to modify existing ggplot objects. This means you can easily set up plot “templates” and conveniently explore different types of plots, so the above plot can also be generated with code like this:

Remember:

- Anything you put in the

ggplot()function can be seen by any geom layers that you add (i.e., these are universal plot settings). This includes the x and y axis you set up inaes(). - You can also specify aesthetics for a given geom independently of the aesthetics defined globally in the

ggplot()function. - The

+sign used to add layers must be placed at the end of each line containing a layer. If, instead, the+sign is added in the line before the other layer,ggplot2will not add the new layer and will return an error message.

Challenge (optional)

Scatter plots can be useful exploratory tools for small datasets. For data sets with large numbers of observations, such as the surveys data set, overplotting of points can be a limitation of scatter plots. One strategy for handling such settings is to use hexagonal binning of observations. The plot space is tessellated into hexagons. Each hexagon is assigned a color based on the number of observations that fall within its boundaries. To use hexagonal binning with ggplot2, first install the R package hexbin from CRAN:

Then use the geom_hex() function:

- What are the relative strengths and weaknesses of a hexagonal bin plot compared to a scatter plot? Examine the above scatter plot and compare it with the hexagonal bin plot that you created.

Building your plots iteratively

Building plots with ggplot is typically an iterative process. We start by defining the dataset we’ll use, lay the axes, and choose a geom:

Then, we start modifying this plot to extract more information from it. For instance, we can add transparency (alpha) to avoid overplotting:

We can also add colors for all the points:

Or to color each species in the plot differently:

Challenge

Use what you just learned to create a scatter plot of weight over species_id with the plot types showing in different colors. Is this a good way to show this type of data?

Boxplot

We can use boxplots to visualize the distribution of weight within each species:

By adding points to boxplot, we can have a better idea of the number of measurements and of their distribution:

Notice how the boxplot layer is behind the jitter layer? What do you need to change in the code to put the boxplot in front of the points such that it’s not hidden?

Challenges

Boxplots are useful summaries, but hide the shape of the distribution. For example, if there is a bimodal distribution, it would not be observed with a boxplot. An alternative to the boxplot is the violin plot (sometimes known as a beanplot), where the shape (of the density of points) is drawn.

- Replace the box plot with a violin plot; see

geom_violin().

In many types of data, it is important to consider the scale of the observations. For example, it may be worth changing the scale of the axis to better distribute the observations in the space of the plot. Changing the scale of the axes is done similarly to adding/modifying other components (i.e., by incrementally adding commands). Try making these modifications:

- Represent weight on the log10 scale; see

scale_y_log10().

So far, we’ve looked at the distribution of weight within species. Try making a new plot to explore the distribution of another variable within each species.

Create boxplot for

hindfoot_length. Overlay the boxplot layer on a jitter layer to show actual measurements.Add color to the datapoints on your boxplot according to the plot from which the sample was taken (

plot_id).

Hint: Check the class for plot_id. Consider changing the class of plot_id from integer to factor. Why does this change how R makes the graph?

Bar graphs

Bar graphs are frequently used for visualizing the number of observations in each category of a categorical variable, or summary statistics (like a mean or median) of a quantitative variable across levels of a categorical variable.

By default, ggplot counts the number of observations in each level and plots those counts on the y-axis. For example, consider plotting the number of each sex in the data set:

Ggplot2 Sheet

However, what if we wanted to visualize the average hind foot length for each sex instead?

We first need to use dplyr to group the data by sex and compute the mean length. We can also filter out the unlabeled sexes:

We now want to map the mean_length variable to the y scale. We must specify stat='identity' inside the geom_bar() command, to specify that we want to use the actual values in the mean_length column on the y-axis instead of the default count:

Challenges

Rstudio Ggplot2 Cheat Sheet

- Create a bar graph that shows the number of each species in each data set. What are the issues with this plot?

- Use

group_by(),summarize(),n()andmean()to create a data set with the species IDs in one column, the number of observations in the second column, and the mean hind foot length in the third column. - Filter this data set to contain only the species with 5 or more entries. Re-create the bar graph showing the count of each species.

- Create a second bar graph showing the mean foot length of each species. Which has the largest? The smallest?

Plotting time series data

Let’s calculate number of counts per year for each species. First we need to group the data and count records within each group:

Timelapse data can be visualized as a line plot with years on the x axis and counts on the y axis:

Unfortunately, this does not work because we plotted data for all the species together. We need to tell ggplot to draw a line for each species by modifying the aesthetic function to include group = species_id:

We will be able to distinguish species in the plot if we add colors (using color also automatically groups the data):

Faceting

ggplot has a special technique called faceting that allows the user to split one plot into multiple plots based on a factor included in the dataset. We will use it to make a time series plot for each species:

Now we would like to split the line in each plot by the sex of each individual measured. To do that we need to make counts in the data frame grouped by year, species_id, and sex:

We can now make the faceted plot by splitting further by sex using color (within a single plot):

Usually plots with white background look more readable when printed. We can set the background to white using the function theme_bw(). Additionally, you can remove the grid:

ggplot2 themes

Ggplot2 Cheat Sheet R

In addition to theme_bw(), which changes the plot background to white, ggplot2 comes with several other themes which can be useful to quickly change the look of your visualization. The complete list of themes is available at http://docs.ggplot2.org/current/ggtheme.html. theme_minimal() and theme_light() are popular, and theme_void() can be useful as a starting point to create a new hand-crafted theme.

The ggthemes package provides a wide variety of options (including an Excel 2003 theme). The ggplot2 extensions website provides a list of packages that extend the capabilities of ggplot2, including additional themes.

Challenge

Use what you just learned to create a plot that depicts how the average weight of each species changes through the years.

The facet_wrap geometry extracts plots into an arbitrary number of dimensions to allow them to cleanly fit on one page. On the other hand, the facet_grid geometry allows you to explicitly specify how you want your plots to be arranged via formula notation (rows ~ columns; a . can be used as a placeholder that indicates only one row or column).

Let’s modify the previous plot to compare how the weights of males and females has changed through time:

Customization

Take a look at the ggplot2 cheat sheet, and think of ways you could improve the plot.

Now, let’s change names of axes to something more informative than ‘year’ and ‘n’ and add a title to the figure:

The axes have more informative names, but their readability can be improved by increasing the font size:

Note that it is also possible to change the fonts of your plots. If you are on Windows, you may have to install the extrafont package, and follow the instructions included in the README for this package.

After our manipulations, you may notice that the values on the x-axis are still not properly readable. Let’s change the orientation of the labels and adjust them vertically and horizontally so they don’t overlap. You can use a 90 degree angle, or experiment to find the appropriate angle for diagonally oriented labels:

If you like the changes you created better than the default theme, you can save them as an object to be able to easily apply them to other plots you may create:

Challange

With all of this information in hand, please take another five minutes to either improve one of the plots generated in this exercise or create a beautiful graph of your own. Use the RStudio ggplot2 cheat sheet for inspiration.

Here are some ideas:

- See if you can change the thickness of the lines.

- Can you find a way to change the name of the legend? What about its labels?

- Try using a different color palette (see http://www.cookbook-r.com/Graphs/Colors_(ggplot2)/).

After creating your plot, you can save it to a file in your favorite format. You can easily change the dimension (and resolution) of your plot by adjusting the appropriate arguments (width, height and dpi):

Note: The parameters width and height also determine the font size in the saved plot.

Page build on: 2017-08-15 10:21:58

Data Carpentry, 2017. License. Contributing.

Startrails for mac. Questions? Feedback? Please file an issue on GitHub.

On Twitter: @datacarpentry